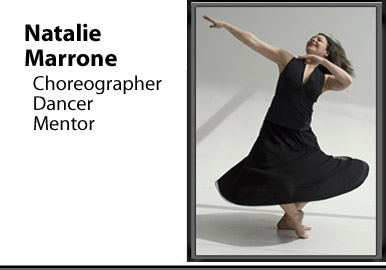

Photo credit: Stephanie Mathews.

Natalie Marrone received her Master of Fine Arts degree in choreography from Ohio State University in 1998. That same year she founded The Dance Cure, a contemporary, all-female dance company based in Columbus, Ohio, and began her field research on southern Italian folk dance. Her work has been recognized by the Congress on Research in Dance, the National Dance Educators Organization, the Greater Columbus Arts Council, the Italian Folk Art Federation, the World Dance Alliance, the American Italian Historical Association, and OhioDance.

Ms. Marrone has served on faculty for ten years in higher-education dance programs and as a guest choreographer and master teacher for universities, public schools, national commercials, live television, and professional academies. In addition to her work with The Dance Cure, she’s currently the jazz dance director of New Albany Ballet Company and recently developed Dance Decisions Inc., a new business that coaches young dancers through the process of choosing a university dance program.

Natalie Marrone on the Web: The Dance Cure, Dance Decisions

Cecil Vortex: Where do you find the inspiration for your choreography?

Natalie Marrone: Eighty percent of the time, the music is what feeds me information. It may not be the music I wind up using, but for me, any kind of inspiration starts with a visceral response to sound and wanting to move to that sound. And the sound isn’t always a beat, although I love rhythm and using polyrhythm. When a soundscape comes on that’s speaking to me, it’s almost like I have a socket and it plugs in and I know that I need to go from there.…

One of the things that always inspires me is a person’s story as it’s written on their body — especially as it’s written on their face. I might not have a job soon if this Botox thing continues. [laughter] I look at people. I look at their physical shape and I look at the way they move. And just for an instant I can almost be inside their being. It’s always something about the story in the lines, the wrinkles — the story of their life is written there. I need to sit at the local coffee shop and just look at people and watch them walk. And feel their walk.… The other thing I really need is in-nature time. I get a lot of sensibility about movement just from the wind sometimes or from sensing the path of wet leaves underneath my feet.

CV: Are there any other day-to-day activities that you’ve found helpful?

NM: Cooking. I remember one time I was on a calzone kick. [laughter] I was in Ohio, missing home. So there I am just trying to do this, and as I’m kneading the dough, I’m simultaneously evaluating what it takes physically to be working a calzone and understanding the sort of physiological structure that I’ve been born with as it’s meant to do certain work, and certain dance, and certain play.

When I’m cooking a lot, I have these moments where I can feel an entire history of people just in the musculature of my body, and an identification with an entire community of people that really has been lost in many ways. So I’m not talking open the jar. I’m talking grow the tomatoes.

CV: Can you talk about the research you’ve done into your culture and the impact that’s had on your choreography?

NM: Well, it was kind of an accident in some ways. I was creating a series of vignettes based on the Italian-American experience and the tarantella — the circle dance that’s always played at Italian weddings, but nobody really knows how to do it. I was making a joke in this work, and all of a sudden it hit me, is there any documentation? I was at Ohio State — the Dance Notation Bureau Library is there. So if the documentation was going to be anywhere, it was going to be right downstairs in the library. There was notation for Chinese dances and Korean dances — all kinds of dances — but nothing for Italian dances. And you’d think, gosh, hasn’t this been covered yet? But the answer was no. And so my first trip to Italy was to figure out what the heck a tarantella really was.…

I wound up going to Puglia to check out these dance forms for myself. And just listening to the music — the old farmer’s music — just hearing the rhythms and feeling the dances in my body, I was completely moved. It felt like my entire heritage had been lost in translation to the United States. And all of the rich, wonderful history of movement that my ancestors would have been doing, I had never even heard about. It was like a blood memory — Martha Graham would call it a blood memory — of my dancing self, my dancing heritage. I realized in those experiences that part of my creativity and part of my gift, whatever gift I’ve got as a dancer, is a responsibility to deliver that information to others here in the United States who’ve also lost what I want to call the dancing textbook of our history. I feel like it’s work that I have to do. Not that it’s painful, but like I can’t not do it.

As a postmodern artist, blending what I know as a choreographer and contemporary dancer with the richness of folk dance has created a place that feels way more authentic in terms of the work that I’m creating and why I’m creating it.

CV: How does thinking about the audience factor into your work?

NM: I’m always very aware of the audience — what [the dance] is going to feel like to the audience, what it’s going to look like to them. I have a really hard time with a lot of dance out there because it can get very self-indulgent. The dance audience is continually dwindling, partially because it’s hard to watch dance if you’ve never danced before. So I’m always thinking about what the hooks are for the audience so that they’re not sitting there going, “Oh God, I have no clue what’s going on and everybody looks really creepy.” [laughter]

One of the really powerful things in my work in the past five years has been that we actually have the audience dance with us…. There was a time when we knew that dancing was a muse, and it was part of life, part of our physical well-being, part of our spiritual connectivity. One of the things for me in terms my work with the audience is that I really don’t want them just sitting there, not feeling the life-giving benefits of dancing, and especially of dancing in a giant circle with a bunch of strangers yelling in Italian. How much better does life get than that? Literally, hundreds of people stand up and start dancing with us.

CV: Wow.

NM: When I go to Italy, and I’m researching these folk dances, it’s the way the grandmother teaches the six-year-old to dance and adjust her shoulders and use her gestures properly so it’s polite while she’s moving — those things are beautiful. And you know, there’s no dialogue. There are some things in the world that are just too fine for talking. And one of them is how dance gets passed on, especially folk dance.

CV: I’ve read that you began choreographing quite young. How did your approach when you were starting out compare to what you learned getting your MFA and what you’re doing now?

NM: My choreography at twelve and my choreography now are actually closer to each other than to any of the work that I was doing in graduate school. I used to say that I had to detox from graduate school a little bit. Not that it wasn’t wonderful training, but it trained a specific voice — a different artistic voice.… You start to figure out how to work inside of a system, but in that time, I sort of lost parts of myself, too.

I’m not saying I was good at editing as a young artist. I think you learn that with training. But my impulses were really powerful and always communicated a very specific idea or character. The more training I got, the more abstract the work got. And it felt kind of out there in the middle of nowhere for a long time.

[Still,] I learned important tools like transposition and editing and changing weight and using space effectively. And now I feel like I’m coming full circle, able to make work that finds those really powerful impulses but also using the craft so that it communicates effectively to the audience.

CV: Is there any advice that you’ve received in your career that stands out as particularly valuable?

NM: I had this teacher once who used to always say, “Make sure you keep up — if you keep up, you’ll be kept up.” I know that sounds kind of weird, but what it means is, keep up with, stay in touch with your work. Because the universe supports you in what you’re meant to do. And if you’re doing what you’re meant to do, and you’re keeping up with the work and keeping up with the investigation that you were meant to do, then you’ll be kept up. It’s that day-by-day interaction with your creative self, I think, that keeps you up, and keeps you fresh.…

I need to keep up. I need to stay in touch. And that doesn’t mean don’t take a break. That doesn’t mean don’t have good boundaries. That doesn’t mean be obsessive. But it means just don’t let that creative part of you slip away mysteriously for a week without giving yourself enough time and space to tap in and speak to those people that need to come through the body this week, whoever they are.

i love dancin 2……wat r the advangtes of being a choreographer……i would love to open my own businees….would it be hard

i love dancin 2……wat r the advangtes of being a choreographer……i would love to open my own businees….would it be hard

I love the way she articulated her creative process…such richness of language that comes alive. Anchored in the sharp awareness and experience of muscle, blood, and movement gives me a real sense of her meaning and in my own Italian body, something is deeply moved.

I like the ‘socket plugging in’ and the piece about the lines, wrinkles and the way people move as expressing a real and unique story about each of us. Love the calzone reference! She obviously is connected to and LIVING the spirit of her work and her being. That, coupled with articulating it in such a way that we, the audience/reader can also have an experience of our own, seems rare. Thanks for sharing the personal insights and processes that assist you in your unfolding self as a dancer and a person!

Good call, C.V. Glad I inserted that “almost!” In fact I’m sure it was Holman’s interview, along with ‘A’ name which places him at the head of my poetry shelf, that made me reach for “Ashbery” instead of, say, Zukofsky in that comment!

Still, I’m intrigued–partly because it’s so different from my own practice, partly because it may point to a valuable departure from the growing ‘professionalization’ of the arts–at how rarely active participation in a field among peers factors into the creative process for the interviewees so far.

This interview was wonderful! Blood memory…identity…it all makes me smile!

Rodney — you might enjoy this quote from Bob Holman’s interview:

“If you need a word, I also suggest going to the bookshelf and saying, well whose word do I need? I find myself often needing a John Ashbery word, so I just go to Ashbery, and I open him up, and I find a word in there that’s going to work. All poets’ vocabularies are distinct, so what kind of word do you need?”

-Cecil

The grandmother in Italy teaching her 6-year-old to dance: esp. appreciated that anecdote. When answering the “where do you go for inspiration?” question, almost no one so far has said they look to other practitioners of their art. Here at least–despite the ‘unlearing’ Natalie feels she’s had to do from her MFA–there’s a recognition that other dancers feed her ideas. Makes me feel better for hauling down the “Ashbery Collected” when I’m low on ideas!

Also, never looked at cooking in quite this way, a form of visceral remembering.

thanks for this interview, natalie and cecil, and for the ongoing message about keeping up.

i liked that about the cooking as well–the physicality of it, the reference to musculature. no surprise that this would be a catalyst for the creation of a kind of work–dance–in which the body is central. but it also reminds me that the creative process, no matter the expression, is not just about an idea forming in interior space but is also a muscular and visceral thing.

A really good, substantial interview. I love the part about making the calzone and being able to put out the tenacles and sort of become the person growing the tomatoes. Very Zen. I’ve been thinking a lot about this lately–how it all comes back to personal identity. I think when we’re younger, the word “creativity” is used as a synonym for escape, mutation, or “proving” something to other people. But she’s tapping into her own history and “blood memory.” I love that!