Photo credit: Image courtesy of Daryl Darko.

Welcome to the conclusion of this three-part interview with guitarist, singer, and songwriter Adrian Belew. If you’re just jumping in, be sure to hop back to the start to hear Belew talk about collaborating with King Crimson and the Bears, why the last two years have been so productive, and how he lets goes creatively.

Adrian Belew on the Web: Adrian Belew.net, Elephant Blog, Side Four

Cecil Vortex: Is there anything you’ve learned about the creative process that’s surprised you?

Adrian Belew: I’m impressed to see that if you work really hard at something, it does eventually pay off. And nothing in my life has proven that to me as much as the creative process. Sometimes you do have to work at it; it doesn’t always just flow out of you like lava. Sometimes you really do have to sit and [say], “How am I going to make this work? What can I do?” And really go deep within yourself or at least concentrate to such a degree that it gets tiring, you know? So I’m kind of amazed that the process works and that it’s still working.

CV: Have you gotten any advice about creativity that particularly stands out?

Conversations about Creativity

An Interview with Adrian Belew, Part Two

Photo credit: Image courtesy of Daryl Darko.

Welcome to the second part of this interview with guitarist, singer, and songwriter Adrian Belew. If you haven’t already read the first part, you can find it here.

Be sure to also check out the third and final segment, in which Belew talks about the value of setting up obstacles, what excites him in other people’s music, and how he recently joined forces with two kids who don’t have driver’s licenses yet to form the Adrian Belew Power Trio.

Adrian Belew on the Web: Adrian Belew.net, Elephant Blog, Side Four

Cecil Vortex: Do you remember when you first started writing songs?

Adrian Belew: At age sixteen I contracted mononucleosis in high school and was forced to stay at home and be tutored for two months. And the requirement was that you be inactive. I was a drummer, and I could no longer drum. I had always had songs in my mind that would just appear, and I could kind of hear them full on as though a record was playing. So I decided to take those two months and teach myself to play guitar.

I borrowed an acoustic guitar from one of my band members, and by the end of the two months I had written five songs and put them on tape. I do remember little bits of pieces of them, but I couldn’t even tell you the melodies or titles.

CV: The tapes are long gone?

AB: I’m afraid so. I wish they weren’t. They’d be on my website right now.

CV: Were you surprised at how quickly you picked up the guitar?

An Interview with Adrian Belew, Part One

Welcome! This interview is part of an ongoing series of chats with artists about their creative process. You can find the full set of interviews, including musicians Van Dyke Parks, Dan Wilson, and Jonathan Coulton, memoirist Ianthe Brautigan, and cartoonist Dan Piraro all at about-creativity.com. You can also subscribe to future interviews here. Thanks a lot for dropping by, -Cecil

Photo credit: Image courtesy of Daryl Darko.

Guitarist, singer, and songwriter Adrian Belew is a Grammy-nominated solo artist and a member of both King Crimson and the Bears. Belew’s big break came in 1977 when he landed a job in Frank Zappa’s band. Over the past thirty years, he’s played on records as varied as David Bowie’s Lodger, Paul Simon’s Graceland, the Talking Heads’ Remain in Light, Herbie Hancocks’ Magic Windows, Nine Inch Nails Downward Spiral, Laurie Anderson’s Mister Heartbreak, and William Shatner’s Has Been. To date, he’s released more than fifteen solo projects, starting with 1982’s Lone Rhino. His most recent CD is Side 4, a live recording of The Adrian Belew Power Trio, a new outfit featuring Julie and Eric Slick on bass and drums.

Belew is currently posting a play-by-play of his ongoing recording efforts mixed with memories from years gone by over at his highly recommended Elephant Blog.

This is the first part of a three-part interview. Be sure to check out part two to hear about how Belew taught himself guitar at 16, what it felt like to sign on with Zappa’s band, and how he writes and performs complex, multi-rhythmic pieces.

Adrian Belew on the Web: Adrian Belew.net, Elephant Blog, Side Four

CV: With both the Bears and King Crimson, you’ve developed longstanding creative relationships that have spanned decades. What do you attribute that to?

AB: When you know something works, you should continue it. There’s a large part of me that’s solo oriented. Like a painter, I think sometimes, “Well, I don’t really need anyone’s help in this. This is me painting a picture or me painting a song.” So as much as I can, I try to do everything myself because that’s not only the most fun, it’s also the most rewarding.

But it’s very healthy to step out of that and share something with someone else where you’re not the only one in control and you’re not the only one with the ideas. Interesting things happen that way. So I’ve tried to kind of have a diet of both throughout my career, as a way to continue to be fresh and grow.

CV: How does collaborative songwriting differ from when you’re writing solo?

AB: Well, most of my collaborative things have been quietly done — you know, one or two people sitting down together, perhaps, unamplified, where you’re just trying to get a basic outline of something. Then you take those ideas away and refine them and you meet again and show each other your refinements.

If I’m working within, say, King Crimson, with Robert Fripp, that’s exactly how it works. It’s a quiet process and what you’re trying to do really is allow each other the freedom to try things and be a sounding board sometimes, or else be the one who’s leading the parade.

CV: So with King Crimson, one person typically takes the lead writing a particular song?

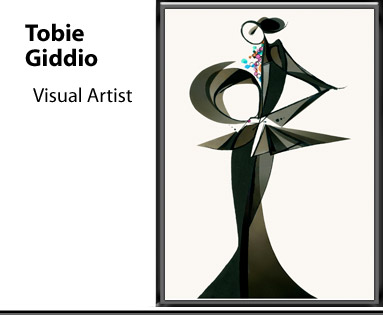

An Interview with Tobie Giddio

Image created for Tiffany & Co. by Tobie Giddio, reproduced courtesy of the artist.

Tobie Giddio grew up on the New Jersey Shore where she fell in love with fashion and art from the books and magazines in her basement makeshift studio. After graduating from the Fashion Institute of Technology, she began illustrating advertisements for Bergdorf Goodman that ran weekly in the New York Times. Other work during this period included editorials for Interview Magazine and elaborately illustrated forecasting books and editorial work for Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue. Since 2000, her work has been commissioned by clients ranging from Seibu Department Stores of Japan, to Apple, Inc., and Tiffany & Co.

Recent projects have included a series of classic charcoal and pen and ink drawings for Amy Sedaris’s book, I Like You: Hospitality Under The Influence and a series of drawings for Infiniti Cars, as well as animated projects with Dovetail Studios, a collaboration between Giddio and her fiancé, motion/graphic designer Peter Belsky.

Tobie Giddio on the Web: Tobie Giddio.com, Dovetail Studios

Cecil Vortex: Can you describe your background?

Tobie Giddio: Well, I started out in fashion illustration. I studied with a number of teachers at F.I.T. [the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York – ed.]. And one of my main mentors was a teacher who was very rooted in fine art, so I was getting taught both principles at the same time. I was learning about drawing, and drawing the figure, and drawing the fashion figure, and then at the same time I was learning how to abstract the figure and learning about color and fine art and especially the modern art folks. To this day, I work in the fashion industry, and I spend a lot of time abstracting fashion and beauty and nature.

CV: How does fashion illustration work — when you’re working on an ad, for example, what are you working from?

An Interview with Dan Wilson, Part Two

photo credit: James Minchin.

Welcome to the second half of this two-part interview with musician Dan Wilson (Trip Shakespeare, Semisonic), whose new solo CD, Free Life, was just released by American Records/Columbia. If you haven’t already read the first part, be sure to check it out to hear about the summer day Wilson wrote his first song, the key role titles play in his songwriting process, and why art is a volume business.

Dan Wilson on the Web: Dan Wilson.com, Dan Wilson on MySpace, Free Life

CV: I’d heard Semisonic’s song “DND” several times before learning that “DND” referred to the “Do Not Disturb” signs in hotels. I wondered what your thoughts were on how much you want to let your listeners in on the particulars behind your lyrics?

DW: This is an important question. I’m torn about it. On the one hand, I’m a talkative guy who has a lot of ideas and they naturally come out in my lyrics. So I often am tempted to explain my songs, or at least tempted to lay out for interviewers (and through them, listeners) the thoughts or ideas or stories behind my songs.

But on the other hand, I have a vivid memory of being a kid and reading an interview with Paul McCartney wherein he said that his song “Jet” was about a dog. Not only that one, but “Martha My Dear,” that one was about a dog, too. These were two songs of his that I loved, and I was just deflated by the revelation — I had had my own mental images of the people in both those songs, not that they were visually detailed, but a kind of “songish” vision of the people and the stories. And to learn that these people were dogs was such a letdown.

Now, Sir Paul has every right to write songs about his dogs, I’ve got no problem with that. But in learning that those particular songs were about dogs, I was suddenly deprived of my own pleasant illusion that they were about people. And somehow they shrank in my mind as a result of being explained.

Another factor in all this is that I often don’t know what the songs are about until long after I’ve written them. This makes it tempting to share the interpretation — since in my mind, my explanation is as good as a listener’s. But on the other hand, once I’ve given my interpretation of my own song, it has the quality of being “the last word.” And sometimes, the fans come up with the coolest interpretations of their meanings – way cooler than the interpretation or intention I might have had.

So I try to curb my impulse to explain my songs, lest I shrink them in the ears of fans.

CV: Is there any aspect of the creative process that still intimidates you?

An Interview with Dan Wilson, Part One

photo credit: Steve Cohen.

Dan Wilson first made his mark with Trip Shakespeare, a Minneapolis-based band featuring Wilson, his brother Matt, bassist John Munson, and drummer Elaine Harris. The four produced a catalog of songs noted for soaring harmonies and a quirky sense of humor that was often matched with an unusual slice of hyper-drama. After Trip Shakespeare, Wilson and Munson teamed up with drummer Jake Slichter to form Semisonic. Throughout the late ’90s and into 2001, Semisonic produced shimmering pop, including the hit song “Closing Time,” nominated for Best Rock Song by the 1999 Grammys.

Since Semisonic, Wilson has worked with musicians ranging from Nickel Creek to Mike Doughty (Soul Coughing). In 2007, he shared the Song of the Year Grammy Award with the Dixie Chicks for their hit tune “Not Ready to Make Nice.” Most recently, American Recordings/Columbia released his long-anticipated solo record, Free Life.

This is the first half of a two-part interview. When you’re done here, be sure to check out the second half, in which Wilson talks about how he wrestles with how little (or how much) to let his listeners in on the particulars behind his lyrics, the benefits of Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies, and the creative challenges he faced mixing his new album.

Dan Wilson on the Web: Dan Wilson.com, Dan Wilson on MySpace, Free Life

Cecil Vortex: What’s the first song you remember writing?

Dan Wilson: I can’t remember the title of the first song I wrote, but I do remember the day. My family was up in northern Minnesota on vacation on this particular clear, hot, summer day. I think I was twelve years old. My parents had bought me a guitar, maybe for my birthday in May.

My parents listened to The Beatles the whole time I was growing up: Sgt. Pepper and Abbey Road. So the first book of sheet music they bought me was Beatles Complete. I think my brother Matt and I had been figuring out the chords in the book all summer. I believe that it was Matt’s idea to write songs — so he wrote one and I wrote one. We did the songs bit by bit over the course of the afternoon on our parents’ bed. In between “songwriting” we’d run out to the ditch by the road and play war with our plastic army men.

When we were done with the songs, we wrote out the lyrics on typing paper, with the titles boldly written on the top of the sheets. Very official. I’m trying to remember them but I can’t. I liked Matt’s more. The lyrics of mine seemed not so great to me. But the melody was satisfying — I remember thinking it sounded like a George Harrison song. Which I guess tells us which Beatle is mine.

I think the impulse came partly from just wanting something to do on a summer day. But also, once you have a bunch of the chords under your hands, you start to realize that “I can do this too.”

I told a painter friend of mine once that the reason I made paintings was often that I’d seen someone else’s painting that I liked, and I wanted to have one for my own. My friend replied that Picasso said the same thing: He’d see a masterpiece in the Louvre and say to himself, “I can do that! I want one of those.”

CV: Did you generally write songs on your own back then, or collaboratively with your brother? And what was your creative process like?

An Interview with Matt Wagner, Part Two

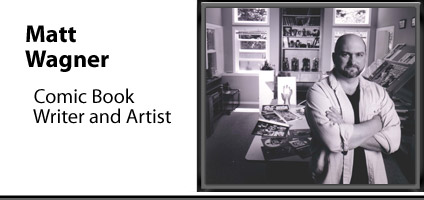

Photo credit: Greg Preston.

Welcome to the second half of this two-part interview with Matt Wagner, award-winning comic book writer and illustrator, and creator of Mage and Grendel. If you haven’t already read the first part of this interview, be sure to check it out to hear Wagner talk about the birth of Mage, and why comic book creations often look like their creators. You can find it here.

Matt Wagner on the Web: mattwagnercomics.com

CV: I recently read your Batman run — the “Dark Moon Rising” books. Could you describe where the idea for those books came from?

MW: They’re actually based on two of my favorite Golden Age Batman stories from the late ’30s and early ’40s. They’re both pre-Robin stories — before Robin shows up. “The Mad Monk” is in Detective Comics #31 and #32. #31 you’ll recognize — it has a very famous cover; it’s a huge image of Batman looming up over a small castle in the foreground. There’s a moon behind him, and he has absolutely ginormous bat ears. In fact, when you look it up, you’ll go, “Oh, of course — that cover.” The other one, “Hugo Strange and the Monster Men,” was in Batman #1.

Part of the fun of playing with somebody else’s toys is the challenge of trying to tell a story where some of the playing pieces are already in place on the board. In the world of Grendel, in the world of Mage, I’m the absolute god. Whatever I say happens, happens, and there’s never any question. With Batman there are many other aspects to consider. [Also,] any work I’ve done for DC, I always like to work early in a character’s career because I hate the giant, extended, huge continuity crap you have to deal with in their world. And I’ve just always liked primary-motivation stories.

So I decided there was a missing link in the early Batman tales, where we needed to see his transition from Batman Year One — the Frank Miller/David Mazzucchelli classic storyline where he’s fighting just thugs and mobsters — to his more established litany of costumed crazies that eventually becomes his absolute normalcy, you want to call it that [laughter]. And so I decided to take these two early stories and revamp them into a modern setting. I wanted to dig deep into the actual origins of this character.

Those early primal Batman tales are neat because the conventions that have since become established as being comic-booky were fresh and new and were based more on a pulp tradition than what we think of as comic cooks. And they were just so unfettered and raw. So I took those and tried to squeeze them into DC’s continuity and make them work.

CV: What’s your creative process when you’re tackling a project like this — what sort of thought bubble might we see over your head while you’re at your desk?

An Interview with Matt Wagner, Part One

Image (c) copyright Matt Wagner.

Matt Wagner is a comic book writer and illustrator, best known for his original comics Mage and Grendel (winner of three Eisner awards) and a five-year run on Sandman Mystery Theater, as well as for recent stints on Batman and on Trinity, a three-issue miniseries featuring Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman.

This is the first half of a two-part interview. Be sure to also check out the second half, in which Wagner talks about how Mage is like a Zen journey, and what makes for good comic-book storytelling.

Matt Wagner on the Web: mattwagnercomics.com

Cecil Vortex: Were you a storyteller as a young boy?

Matt Wagner: I was. My father, and this dates him quite a bit, used to say I was vaccinated with a Victrola needle because I was very talkative…. My parents like to tell a tale of when I was quite young. I must have been five or something like that. We had literally — I kid you not — a door-to-door Bible salesman come to the door one day selling these lavishly illustrated Bibles. We were going through it and I was pointing out all the illustrations and saying, “Oh, look this is Noah, this is Jonah, Jesus” etc., etc., and we got to a picture of Adam and Eve in their loincloths in the Garden of Eden and I turned to my dad, apparently, and said, “Dad, Tarzan!” [laughter] So I think I was doomed for this profession from the very beginning.

My mother was an English teacher before she became a full-time mom, and a huge proponent of reading, so she made sure I was an early and vigorous reader. Coupled with that was the fact that I was an only child. I grew up in the middle of Pennsylvania in Amish country — we lived out away from most other houses…. I drew to entertain myself because there wasn’t much video entertainment in those days. I think we had probably three or four TV stations initially. And so I was a vigorous reader and I drew. And comic books were both writing and drawing all rolled into one and just became the magic quotient for me.

CV: So you were headed for comics from the start?

“About-creativity.com, I choose you!”

Woke up this morning to find that some wonderful human being over at Yahoo had selected us as Yahoo Picks’ “Pick of the Day.” If you’ve discovered this site through that review, welcome!

The artist interviews to-date include: poets Kim Addonizio, Maggie Nelson, and Bob Holman, web innovator Ze Frank, musicians Jonathan Coulton and Van Dyke Parks, choreographer Natalie Marrone, authors Lemony Snicket and DyAnne DiSalvo, visual artists James Warren Perry and Tucker Nichols, clown and playwright Jeff Raz, standup comic and sitcom writer Howard Kremer, cartoonist Dan Piraro, columnist Jon Carroll, and screenwriter/director John August. Scroll down to peruse the interviews from most recent to least-most-recent.

You can also subscribe to future interviews — I’ll be posting a new one every week or two. Upcoming interviews include comic book creator (Mage/Grendel) Matt Wagner, musician Adrian Belew, and World of Warcraft storyteller Chris Metzen.

Thanks a lot for dropping by. If you get a chance, be sure to leave a comment to let us know what you think,

-Cecil

An Interview with Kim Addonizio

Photo credit: Joe Allen.

Kim Addonizio is the author of three books of poetry from BOA Editions: The Philosopher’s Club, Jimmy & Rita, and Tell Me, which was a finalist for the 2000 National Book Award. Her latest poetry collection, What Is This Thing Called Love, was published by W. W. Norton in January 2004. A book of stories, In the Box Called Pleasure, was published by Fiction Collective 2. She’s also coauthor, with Dorianne Laux, of The Poet’s Companion: A Guide to the Pleasures of Writing Poetry (W.W. Norton). And her new novel, My Dreams Out in the Street, has just been published by Simon & Schuster.

Addonizio’s awards include two fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Pushcart Prize, a Commonwealth Club Poetry Medal, and the John Ciardi Lifetime Achievement Award. She teaches private workshops in Oakland, CA.

Kim Addonizio on the Web: kimaddonizio.com, My Dreams Out in the Street, What Is This Thing Called Love

Cecil Vortex: When did you first start to identify yourself as a writer?

KA: I remember my first unfinished work. I wanted to write a novel when I was around nine. I wrote ten pages. It was a mystery, I think. I don’t remember why I stopped — probably because it was too hard. I remember writing a short story at fifteen and being eager to show it to my dad, who was a sportswriter.

CV: Do you remember what drew you to writing poetry?

KA: I wrote down my feelings in lines in high school and after, but it was hardly poetry. I seriously started trying to write it in my late twenties. I think poetry drew me to it — I think I was always meant to find it.

CV: How has your creative process changed since then?